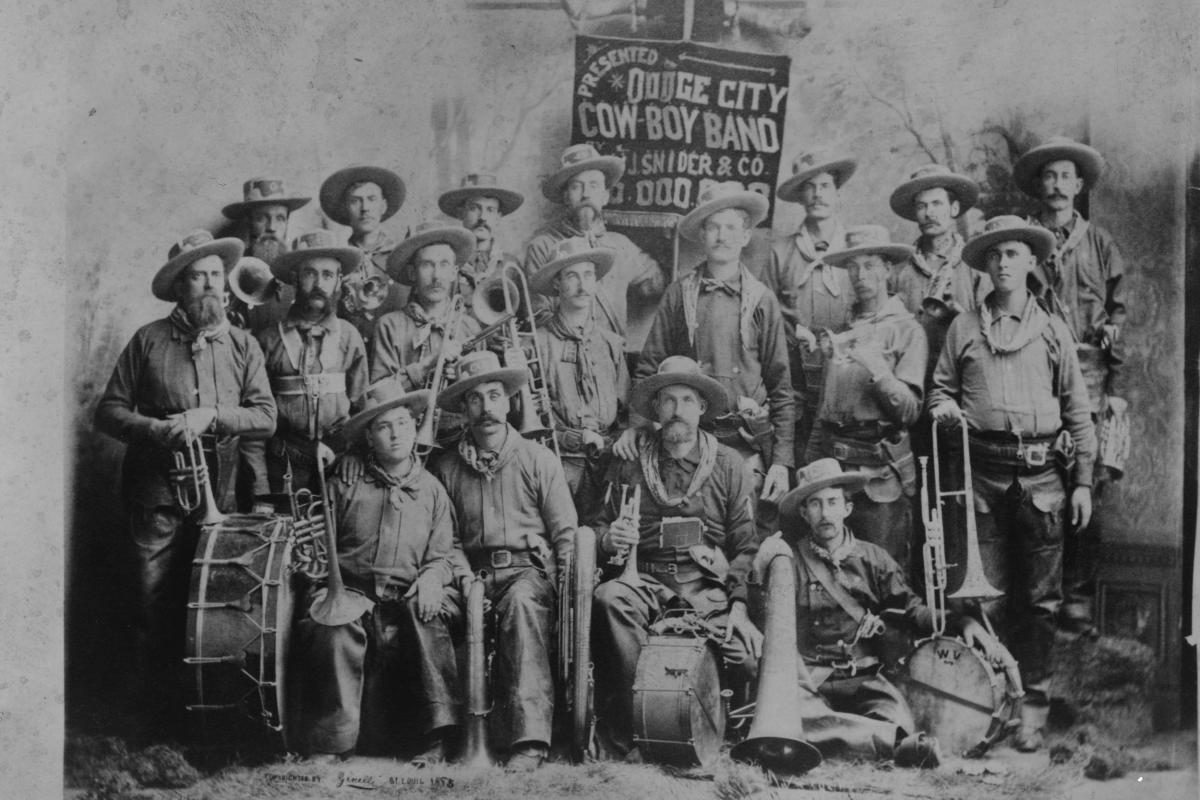

150 years ago, Texas cowboys began driving cattle herds along the newly established Western Cattle Trail and transformed Dodge City with their business, celebrations, and wild ways

This year marks the 150-year legacy of the Western Cattle Trail, also known as the Texas Trail or the Dodge City Trail, a cattle industry road connecting Texas ranchers with Midwestern railroad depots and processing centers. Originating in 1874, the trail shaped the nation’s westward expansion and the development of Kansas, particularly Dodge City.

With the end of the Civil War in 1865, Texas cattlemen could market their cattle to prosperous and populous Northern towns, but they faced a formidable task in driving their cattle to these thriving markets. The ranchers had no direct railroad connections, and driving the cattle all the way to market was impractical because towns and communities were in the way and the cattle would lose too much weight from the lengthy journey. Their best solution was to walk the cattle to the nearest railroad shipping point, usually in Kansas, and then ship the cows the rest of the way.

The first route they created was the Shawnee Trail, running from Texas to Kansas City, but expanded settlements and farmland soon made that trail impassible. The ranchers then followed the Chisholm Trail, leading into Abilene.

Following the conclusion of the Red River War in early 1875 and the punitive relocation of the Comanche and Kiowa onto reservations, more settlers poured into central Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and the Texas Panhandle. This influx of farmers and ranchers, coupled with the Quarantine Law of 1875, forced Texas ranchers to drive their cattle further west and pick up a trail established just one year prior by John T. Lytle, an experienced cattle driver. This route brought cattle to the railheads in Kansas and Nebraska along a more western but still practical route.

The Trail’s Most-Traveled Years

This Western Cattle Trail quickly became a pivotal component of the cattle-driving industry. It originated in the hill country of Texas near present-day Kerrville and branched off at several points northward, including Dodge City.

Originally, Dodge City was founded partly due to buffalo hunting. However, the hunting started only after the buffalo became nearly extinct due to mass slaughter. At this point, Dodge City needed another source of income to survive.

The sighting of the first large trail herds at the Point of Rocks on the outskirts west of Dodge City in 1874 sparked hopes and schemes for a significant economic boom.

The cowboys who drove these herds spent two or three months traveling at cattle-pace of about 12 miles a day. With their remarkable resilience, their hardy longhorns grazed for food and paced themselves by instinct.

The cowboys had other instincts.

By the time they reached Dodge City, they were ready for a good time, and had some money to make it possible. The 15 or so men employed on the average drive were each paid $30 to $40 a month—and Dodge City was there to give them what they wanted.

Saloon keepers catered to the prospects of cowboy coin by giving their establishment a Texas flavor with names such as Nueces, Alamo, and Lone Star.

But it wasn’t just drink.

After enduring a month or two on the trail, battling dust, heat, storms, and elevated water and subsisting on coarse meals, which often consisted of beans, bacon, and coffee, the cowboys looked forward to well-deserved leisure. Arriving at a town at trail’s end, a cowboy first bathed, shaved, and donned a fresh outfit—likely including quilted-top, tight-fitting dress boots with the pronounced lone star at the top and a new Stetson 10-gallon hat.

Many also got rowdy, sometimes fighting over money, a woman, or some unfinished business from the journey. These altercations, while sometimes resulting in gunfights, were a regular part of cowboy life and became part of the Wild West’s mystique.

To keep the cowboys from simply bypassing the city, the merchants of Dodge stocked their shelves with goods a cowboy might need. Merchant and civic leader Robert Wright advertised his store as a haven of abundance, offering “the largest and fullest line of groceries and tobacco west of Kansas City.” His store also provided groceries, clothing, Studebaker wagons, Texas saddles, rifles, pistols, Bowie knives, and building hardware.

As the cattle-shipping season of 1876 loomed, the Santa Fe Railroad Company quickly built a sizeable new stockyard in Dodge City, and civic leaders assured the drovers that Dodge was ready for them. The first great herd from Red River arrived in Dodge on May 12, 1877, and from that day, Dodge City became a full-fledged cattle town.

The Western Trail was paramount in transporting an estimated 3–5 million longhorns, of which an average of 75,000 head of cattle were shipped out of Dodge City annually from 1875 through 1885. The last recorded herd to use the trail was in 1897 when John McCandless drove his herd from the Texas Panhandle XIT ranch, the largest fenced ranch in the world at that time. McCandless, a cowboy turned Texas Ranger, a steadfast trail boss, led his ranch’s last big cattle to drive as the syndicate was shutting down operations in Texas and selling off the remaining land.

The Cowboys Who Rode It

Much of what we know about life on the trail—and just off of it—comes from accounts by the cowboys who rode it. Andy Adams, Reed Anthony, Charles Siringo, and Nat Love are just some who left behind vivid, colorful memories and first-hand accounts. Jack Potter, a traveler who rode the rail system into Dodge City, wrote in “Coming Off the Trail in ’82” about the nightlife he experienced while making a short layover.

That night at twelve o’clock, we reached Dodge City, where I had to lay over for twenty-four hours. I thought everything would be quiet in the town at that hour of the night, but I soon found out that they never slept in Dodge.

They had a big dance hall there which was to Dodge City what Jack Harris Theater was to San Antonio. I arrived at the hall in time to see a gambler and a cowboy mix up in a six-shooter duel.

Contrary to popular belief, the cattle drive was not a slow, mundane journey. It could be an adrenaline-pumping adventure filled with danger. Stampedes, a constant threat, could be triggered by thunderstorms, prairie dog holes, and sheer fatigue from the journey. The terrain could change dramatically, especially when crossing several rivers during the spring flooding season. Cowboys not only had to be skilled riders and ropers but also had to be prepared to navigate encounters with wolves, farmers, and Indigenous people, who often saw the cattle drives as an affront to their way of life. They also confronted the looming threat of cattle rustlers, who would have no qualms about killing a cowboy to take the herd.

Cowboys rode the Western Cattle Trail for less than 25 years in all, but the heritage of the Western Cattle Trail can still be seen today in the Western United States, with historical markers, museums, and annual events commemorating its significance. The trail continues to captivate the imagination of people around the world, serving as a reminder of a short-lived, bygone era when cowboys drove their herds north to the cities, arriving with stories, plenty of dust, and pockets full of pay.

The Kansas Portion of the Western Cattle Trail

Running from South Texas to Nebraska, the Western Cattle Trail crossed from the south to the north border of Kansas. Just before entering Kansas from the south, the trail went directly northwest of May, Oklahoma, where it crossed the Beaver River (also known as the North Canadian River), fording on the sand bar at the mouth of Clear Creek. The trail then passed near Laverne and Rosston and entered Kansas just east of the Cimarron River, striking across the stream at Deep Hole Crossing. At Deep Hole, the cowboys sometimes stopped at Red Clark’s Long Horn Round-up Saloon just before traversing the Cimarron River.

Continuing north to Dodge City, the trail veered slightly eastward from the Cimarron River to the south side of the Arkansas River and into the vast grasslands to fatten the cattle. If cattle were to be sold, the final section crossed into Dodge City over the Arkansas River northward to the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway railhead stock pens. On many occasions, after the cowboys visited Dodge City, the cattle herds continued to travel north into Nebraska, where they often could find a better market in Ogallala. This trek took them over the Kansas line in Rawlins County, where they met the challenge of the Republican River. Notably, not all cowboys took the same route north. Kansas historians Gary and Margaret Kraisenger have documented three separate trail branches into Nebraska.

Learn More

To learn more about the Western Cattle Trail and life in Dodge City during the heyday of the cattle trails, visit the Boot Hill Museum in Dodge City. Keith Wondra, the curator at Boot Hill Museum, states that “Dodge City’s economy has always revolved around the cattle trade. The permanent cattle trail exhibit at Boot Hill Museum depicts the agencies required for processing and looking after the cattle. It also features a hand-painted mural that brings longhorns to life as they emerge from it.”

Boot Hill Museum

500 W Wyatt Earp Blvd

Dodge City

620.227.8188 | boothill.org